By the time the young, nameless woman was pulled from the Seine, the Paris Morgue had long been a place of morbid spectacle. It was near the turn of the century, but since 1867 the unidentified dead had been brought to the morgue near the river for public display. Initially meant as a place for loved ones to find and claim their missing, the Paris Morgue had become a well-known attraction for tourists and locals alike. For 40 years it had been free and open to the public, a place for the living to survey the corpses, to speculate on who they were and why they may have ended up behind the glass, naked on a cold marble slab waiting for someone to love them enough to find them and lay them to rest.

Many of them were suicides, and many came out of the river, but all manner of ends were met, and all ages were represented in various states of ruin. She was not like the others though. She had no marks or injuries at all. Some said she drowned herself in the river. “Si tragique! But why?!” Of course, there was no way to know for sure, but the beauty of a beguiling nameless corpse is that you can project whatever fantasy you want onto her life, yet the mystery will always keep you reaching and yearning for a knowing.

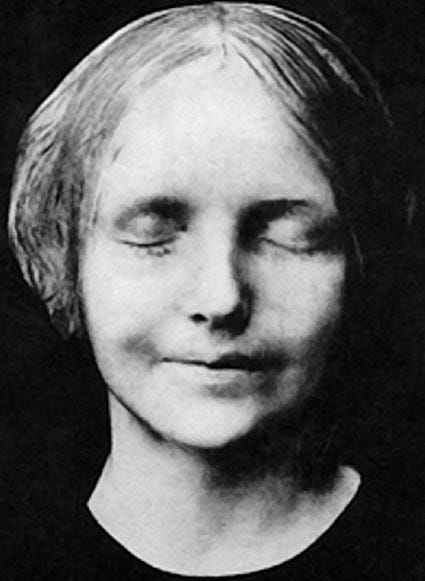

Or, maybe the very idea of her, flawless both in her youth and in her death, her face expressing a slight smile that seemed to hold a secret from the other side, was created as a "trés jolie lègende"—a very pretty legend. One that has permeated a century. Yet, if you look closely, the reality of L'Inconnue de la Seine’s story is as uncertain as the names and killers of the morgue attractions.

Though death masks were not always done for those that ended up in the Paris Morgue, the legend holds that one pathologist was so stricken with her beauty, he hired a caster to create her death mask which forever captured the serenity of her last moments. Replicas of the mask went on to grace the walls of those enchanted by her tragic story for decades. Her body, they say, was never claimed, yet no records have been found to verify this particular young woman was ever at the morgue.

Claire Forestier, a descendant of the Lorenzi family model-makers, where the original death mask of L'Inconnue de la Seine resides today, has serious doubts. “Look at her full, rounded cheeks, her smooth skin. There is simply no way the cast could have been taken from a corpse,” she told The Guardian in 2007. “And this is certainly not a drowned woman, fished from the water. It would be impossible to take such a perfect face from a dead woman.”

A description of the Paris Morgue from 1885 makes it seem unlikely that such a serene specimen could exist among the stars of that grotesque show, but then again, if she did exist, it’s also clear why her contrasting condition would have captured the imagination:

”Brutal, gashed, and swollen faces; wide gaping mouths, which opened for the last time to utter the death-shriek, and are now fixed forever in rigid agony; jagged, discolored teeth, sunken cheeks, knitted brows, dead, sodden eyes, awful contortions, ghastly smiles, hideous leers, faces of men and faces of women, faces of the young and faces of the old, faces which reek with the slime of years of vice and misery and despair; faces which Dante, groping among the damned, might have dragged from hideous, steaming depths of Lethean mud, and flung forth to front the unwilling eye of day; faces mutilated into every shape into which the human countenance can be bruised or flattened or slashed or puffed or putrified,-such is the sight which greets the visitor upon his entrance to the Paris Morgue.”

Upon arrival, the bodies were stripped, washed, and inspected for any clues to their causes of deaths or identities. Next, they were frozen solid before being rolled out on slabs, which were tilted up for the public to view. They lay in two rows of about 12 to 16 corpses, depending on the source, in a refrigerated theater behind a glass partition. Long heavy curtains were tied on either side of the large window. From dawn to 6 p.m., seven days a week, people came.

Some carried the nauseating fear that they may find who they were looking for, others just came to see; to be repulsed, fascinated, mournful, shocked, and even titillated by seeing the often naked forms. Loin cloths were in place, but it was uncommon for people of the time to see so much skin, so much open aching humanity. The clothes of the nameless dead hung near their bodies, offering clues to their stations in life.

When people heard of the more unusual cases, like a beheaded woman, or small children, they came in droves. If they’d read about a murder in the newspaper, they would go see if the victim was anyone they knew. Families took their children, society ladies went for outings at the morgue and bonded over their sadness and wonderment about the fortunes of the “macchabées.” It was said that murderers may be lurking, tantalized to see their handiwork.

In part, it was morbid curiosity that pulled people there. Still, they also viewed it as a way of bearing witness, of trying to help identify the dead, and of “solidarity born out of tragedy,” per JSTOR Daily. The Supplement illustre de petit journal explained it like this: “We all loved each other for a few hours because we cried together: why can we not continue to do so?” However, concern for the moral hygiene of those who couldn’t resist the macabre scene— particularly the women and children—was the number one critique of the morgue.

The young woman was thought to be 16, or maybe she was 20. Impossible to know for sure. Like the others, she would have been on display for about three days and if unclaimed, the unfortunates became cadavers for medical students to learn from. Some would be photographed or have a wax cast made of their faces before their next roles, but the bodies had to be moved along.

In her case, as the story goes, the caster who captured her serenity in death hung the mask on the wall in his shop. People were drawn to it, artists, writers, dreamers, and the like. Copies were made. She was the Ophelia of the Seine, the drowned Mona Lisa. She served as a muse, the tragic mystery of the peaceful girl lured them in, lured us all in.

Throughout the early 20th century, it was not uncommon to see the mask of L'Inconnue de la Seine decorating homes or artist studios. She inspired poetry and novellas. She inspired thought and melancholy. And yet, those who have tried to prove she was real have never been able to do so. Was she a living girl when the mask was made, as presumed by a master caster? Or, as another master mold maker told The New York Times in 2017, “Maybe the mold was taken before her facial muscles began to fall. Maybe. Maybe.” Was the whole story a "trés jolie lègende" as an archivist suggested? Much like the names of the unclaimed at the Paris Morgue, we’ll never know.

In 1907, the morgue finally closed, but the unknown woman’s face, in a strange twist, found a name. Today, L’inconnue’s likeness lives on in Resusci Anne, the ubiquitous female CPR training mannequin. How that came to be, however, is another story.

Sources not linked in the text:

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/55611/the-morgue-charles-meryon

https://bonjourparis.com/history/the-paris-morgue-a-gruesome-tourist-attraction-in-19th-century/

https://www.edwardianpromenade.com/amusements/the-morbidity-of-the-paris-morgue/

https://www.sciencehistory.org/stories/disappearing-pod/the-mona-lisa-of-the-seine/

I’m a total history nerd, especially when it’s dark and morbid like this. That morgue…what a source for writing inspiration. A story in every corpse.

Love this piece and the morbid curiosity we seldom admit to. Today, in most modern lives death is removed and sanitized.